Paste has been in existence since July 2002, but it’s taken 22 years for us to sit down and make a “Greatest Albums of All Time” list. Every reputable outlet has done this at some point or another; each magazine piecing together a vastly different collection of picks. Doing a list like this is a fool’s errand for the most part, as picking any number of records and labeling them “the best” is subjective and likely wrong—but, if the internet has taught us anything, it’s that we all love to tap in, disagree and hold discourse. It’s the lifeblood of criticism and art forms with canons that are diverse and extensive, and the history of popular music spans decades: from Depression-era radio through the Moondog Coronation Ball birthing rock ‘n’ roll in Cleveland in 1952 through the British Invasion through the alt-rock explosion of the 1990s to now, as Taylor Swift and Beyoncé are monolithic in a global ecosystem of sights and sounds. The criteria for what constitutes a “great album,” to us, falls someplace in-between influence and timelessness. That’s how you get a list featuring the Talking Heads, Death, Mariah Carey and Lana Del Rey.

For this list, we called on our entire writing cohort—including editors, staff writers, interns and freelancers far and wide—to send in their individual Top 20 lists. We then took those lists, along with editorial oversight, and compiled what we believe is a selection of music that represents what Paste believes is the best to have ever been recorded. Our picks are subjective, and we aren’t going to sit back and consider this list some end-all, be-all document. Truthfully, we had a lot of fun putting this whole thing together and considering what music has been so definitive to us as a publication over the last 22 years. Now, we can’t wait to hear what you all think. (See the end of our list for a mix of our favorite songs from the 300 greatest albums of all time.)

Contributors: Matt Mitchell, Olivia Abercrombie, Josh Jackson, Garrett Martin, Robert Ham, Grant Sharples, Niko Stratis, Sam Rosenberg, Devon Chodzin, Hayden Merrick, Elizabeth Braaten, Elise Soutar, Matty Pywell, Tom Williams, Matt Melis, Ellen Johnson, Victoria Wasylak, Sean Fennell, Annie Nickoloff, Andy Steiner, Eric R. Danton, Annie Parnell, David Feigelson, Taylor Ruckle, Natalie Marlin, Madelyn Dawson, Ben Salmon, Ted Davis, Alex Gonzalez, Pat King, Wyndham Wyeth, Jeff Gonick, Grace Ann Natanawan, Doug Heselgrave, Holly Gleason, Ryan Burleson, Bonnie Stiernberg, Max Blau, Leah Weinstein

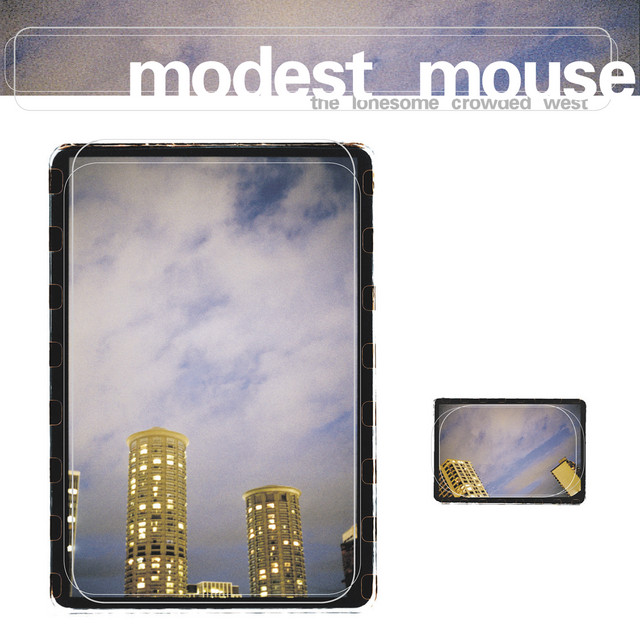

300. Modest Mouse: The Lonesome Crowded West (1997)

It’s been over 25 years since the release of Modest Mouse’s iconic second album, and few indie-rock records in the decades since have managed to blend the chaotic showmanship, enduring hooks and lasting vision present in the 78-minute opus. As vast, gnarly and, at times, as downright ugly as its namesake, this is a record where an Orange Julius is made as holy as God’s shoeshine and a Saturday night with Cowboy Dan doing the co*ckroach is the height of culture. Frontman Isaac Brock and his bandmates have made many good to great records, but it is The Lonesome Crowded West that captures their vision of a warped American Dream most succinctly. —Sean Fennell

It’s been over 25 years since the release of Modest Mouse’s iconic second album, and few indie-rock records in the decades since have managed to blend the chaotic showmanship, enduring hooks and lasting vision present in the 78-minute opus. As vast, gnarly and, at times, as downright ugly as its namesake, this is a record where an Orange Julius is made as holy as God’s shoeshine and a Saturday night with Cowboy Dan doing the co*ckroach is the height of culture. Frontman Isaac Brock and his bandmates have made many good to great records, but it is The Lonesome Crowded West that captures their vision of a warped American Dream most succinctly. —Sean Fennell

299. Rihanna: Anti (2016)

By the time Rihanna released her eighth album, she’d never really captured a complete, well-rounded project. Rated R, Loud and Unapologetic were all good, but caught themselves illuminated by the successes of hit singles rather than a full-bodied cohesion. But Anti changed all of that in 2016. Songs like “Work,” “Love on the Brain” and “Needed Me” remain bombastic fusions of hip-hop, soul, dancehall and psychedelia, and deeper cuts like “Desperado,” “Consideration” and “Higher” are massive earworms toned by lo-fi beats and cross-tempo vocalizations and arrangements. As a whole, Anti didn’t make itself out to be a radio-friendly smash hit; Rihanna leaned into her superstardom by exploring sonic eclecticism and penning tracks that reached into the pockets of desire, alcohol and relationships, both through betrayal and empowering love. It’s the kind of career-triumph that few artists of the last 25 years have had. —Matt Mitchell

By the time Rihanna released her eighth album, she’d never really captured a complete, well-rounded project. Rated R, Loud and Unapologetic were all good, but caught themselves illuminated by the successes of hit singles rather than a full-bodied cohesion. But Anti changed all of that in 2016. Songs like “Work,” “Love on the Brain” and “Needed Me” remain bombastic fusions of hip-hop, soul, dancehall and psychedelia, and deeper cuts like “Desperado,” “Consideration” and “Higher” are massive earworms toned by lo-fi beats and cross-tempo vocalizations and arrangements. As a whole, Anti didn’t make itself out to be a radio-friendly smash hit; Rihanna leaned into her superstardom by exploring sonic eclecticism and penning tracks that reached into the pockets of desire, alcohol and relationships, both through betrayal and empowering love. It’s the kind of career-triumph that few artists of the last 25 years have had. —Matt Mitchell

298. Queen: Jazz (1978)

The two songs I first remember sticking with me from my mom’s Queen Greatest Hits CD were the absurd, catchy lyricism of the sonic siblings “Fat Bottomed Girls” and “Bicycle Race”—there was nothing funnier to my six-year-old self than a guy fervently proclaiming he wants to ride his bicycle. Jazz continues the ridiculous lyrics with “Don’t Stop Me Now,” which is just Freddie Mercury going on and on about being a “sex machine.” However, it is often interpreted as a song about perseverance—which fits right into the hilarity Jazz achieves. The record is also iconic for being tagged as a “fascist” record by Rolling Stone upon its release. Jazz showcases an exorbitantly confident Queen, who are playful and campy in a way that encapsulates an entire career of pushing boundaries and prioritizing their unique sense of humor. —Olivia Abercrombie

The two songs I first remember sticking with me from my mom’s Queen Greatest Hits CD were the absurd, catchy lyricism of the sonic siblings “Fat Bottomed Girls” and “Bicycle Race”—there was nothing funnier to my six-year-old self than a guy fervently proclaiming he wants to ride his bicycle. Jazz continues the ridiculous lyrics with “Don’t Stop Me Now,” which is just Freddie Mercury going on and on about being a “sex machine.” However, it is often interpreted as a song about perseverance—which fits right into the hilarity Jazz achieves. The record is also iconic for being tagged as a “fascist” record by Rolling Stone upon its release. Jazz showcases an exorbitantly confident Queen, who are playful and campy in a way that encapsulates an entire career of pushing boundaries and prioritizing their unique sense of humor. —Olivia Abercrombie

297. Terry Riley: A Rainbow in Curved Air (1969)

Terry Riley is often lumped in with 20th Century minimalists, like Philip Glass and Steve Reich. But where those artists aimed to reinvigorate classical techniques, Riley’s work is more heady and colorful. His 1969 record, A Rainbow In Curved Air, isn’t just an ambient masterpiece; it’s a tour de force in psychedelia. After spending years working to recontextualize orchestral instrumentation, A Rainbow In Curved Air found Riley playing into bohemian tropes of the era. Across two compositions that both hover around the 20-minute mark, fluttering synthesizer and harpsichord melodies are permeated by fleeting tambourine and hand drum rhythms, as well as innovative tape effects. The original cover art featured a poem by Riley, imagining America toppled by utopianism—reinforcing A Rainbow In Curved Air’s place as one of the most upward-gazing records ever. —Ted Davis

Terry Riley is often lumped in with 20th Century minimalists, like Philip Glass and Steve Reich. But where those artists aimed to reinvigorate classical techniques, Riley’s work is more heady and colorful. His 1969 record, A Rainbow In Curved Air, isn’t just an ambient masterpiece; it’s a tour de force in psychedelia. After spending years working to recontextualize orchestral instrumentation, A Rainbow In Curved Air found Riley playing into bohemian tropes of the era. Across two compositions that both hover around the 20-minute mark, fluttering synthesizer and harpsichord melodies are permeated by fleeting tambourine and hand drum rhythms, as well as innovative tape effects. The original cover art featured a poem by Riley, imagining America toppled by utopianism—reinforcing A Rainbow In Curved Air’s place as one of the most upward-gazing records ever. —Ted Davis

296. The Raincoats: The Raincoats (1979)

A favorite of anyone with a Kat Stratford obsession, the Raincoats were a driving force in the female-led punk movement, and their self-titled debut cemented them as icons of feminist punk. In 1979, they released The Raincoats, an experimental DIY rock record with Ana da Silva and Gina Birch’s vocal sass dueling with a playful intensity. Their debut became a cornerstone for many “riot grrrl” bands for its unapologetically messy production, off-kilter rhythms and vulnerable yet snarky lyricism. Palmolive’s frenzied drumming style paired with da Silva’s jerky guitar are a match made in DIY heaven, notably for how their chaos intertwines with the melodic bass grooves of Birch. It’s a seamless combination of musicality and havoc. —Olivia Abercrombie

A favorite of anyone with a Kat Stratford obsession, the Raincoats were a driving force in the female-led punk movement, and their self-titled debut cemented them as icons of feminist punk. In 1979, they released The Raincoats, an experimental DIY rock record with Ana da Silva and Gina Birch’s vocal sass dueling with a playful intensity. Their debut became a cornerstone for many “riot grrrl” bands for its unapologetically messy production, off-kilter rhythms and vulnerable yet snarky lyricism. Palmolive’s frenzied drumming style paired with da Silva’s jerky guitar are a match made in DIY heaven, notably for how their chaos intertwines with the melodic bass grooves of Birch. It’s a seamless combination of musicality and havoc. —Olivia Abercrombie

295. Bad Brains: Bad Brains (1981)

Recording the Bad Brains in the early ‘80s must have been like trying to photograph the moment a tornado touches down. By the time the punk pioneers committed this self-titled record to tape, they’d already inspired a generation of DC bands and decamped to New York City, ready to strum stormy circles around their counterparts, the Ramones. The Yellow Tape, as it’s also known, isn’t their cleanest work of this era—they had a Ric Ocasek-produced LP on the way a year later—but it may be the most impactful document of the Bad Brains’ early efforts to push punk and reggae fusion past the limits of shrieking speed and spirituality. It remains undisputed hardcore canon, but in another few years, they were already “Sailin’ On” to more ambitious genre blends. —Taylor Ruckle

Recording the Bad Brains in the early ‘80s must have been like trying to photograph the moment a tornado touches down. By the time the punk pioneers committed this self-titled record to tape, they’d already inspired a generation of DC bands and decamped to New York City, ready to strum stormy circles around their counterparts, the Ramones. The Yellow Tape, as it’s also known, isn’t their cleanest work of this era—they had a Ric Ocasek-produced LP on the way a year later—but it may be the most impactful document of the Bad Brains’ early efforts to push punk and reggae fusion past the limits of shrieking speed and spirituality. It remains undisputed hardcore canon, but in another few years, they were already “Sailin’ On” to more ambitious genre blends. —Taylor Ruckle

294. Deulgukhwa: 들국화 (1985)

Deulgukhwa’s debut studio album is a masterful entry into South Korea’s rock pantheon, dropped right into the middle of the country’s pop music renaissance in the mid 1980s. March is the only album Deulgukhwa made that features their OG lineup (Jeon In-kwon, Choi Seong-won, Jo Deok-hwan, Heo Seong-wook), and it sounds like a perfect amalgam of the chart-topping arena music of its era and the jaw-dropping hooks of modern K-pop. “That’s My World” blisters along with a head-splitting guitar solo from Deok-hwan enveloped by Seong-won’s synthesizers. In-kwon establishes himself as one of the greatest Korean frontmen of all time, belting stadium-sized vocals with a backdrop of anthemic technicolor from Deok-hwan and drummer Joo Chan-kwon. The sublime, sugar-sweet euphoria of “Bless You” pairs nicely with the acoustic, piano-pillowed balladry of “Just Love,” and “Until the Morning Rises” is the kind of crooner bravado replicated later in the decade by English-language great George Michael on something like “One More Try.” March sounds as epic as anything American and English pop rock was producing at the same time, perhaps even more so. —Matt Mitchell

Deulgukhwa’s debut studio album is a masterful entry into South Korea’s rock pantheon, dropped right into the middle of the country’s pop music renaissance in the mid 1980s. March is the only album Deulgukhwa made that features their OG lineup (Jeon In-kwon, Choi Seong-won, Jo Deok-hwan, Heo Seong-wook), and it sounds like a perfect amalgam of the chart-topping arena music of its era and the jaw-dropping hooks of modern K-pop. “That’s My World” blisters along with a head-splitting guitar solo from Deok-hwan enveloped by Seong-won’s synthesizers. In-kwon establishes himself as one of the greatest Korean frontmen of all time, belting stadium-sized vocals with a backdrop of anthemic technicolor from Deok-hwan and drummer Joo Chan-kwon. The sublime, sugar-sweet euphoria of “Bless You” pairs nicely with the acoustic, piano-pillowed balladry of “Just Love,” and “Until the Morning Rises” is the kind of crooner bravado replicated later in the decade by English-language great George Michael on something like “One More Try.” March sounds as epic as anything American and English pop rock was producing at the same time, perhaps even more so. —Matt Mitchell

293. Ice Cube: AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted (1990)

After walking away from N.W.A., the L.A. group that instantly put him in the upper echelon of lyricists and rappers, Ice Cube spent some time in New York, holed up in the studio space of production team the Bomb Squad. He went through their voluminous record collection looking for inspiration and what would become the sound of his first solo album. What they landed on was an album that carried the same density as the Squad’s other famous collaborators Public Enemy but was much more funky. The feel of the beats loosened Cube’s tongue considerably. He remained true to the storytelling vibe he established on Straight Outta Compton with his clear-eyed perspective on life in South Central L.A. but developed a leaner pugnaciousness that helped fuel the war on words with his former partners and cut down to size the fools that dared to question his skills and strength. —Robert Ham

After walking away from N.W.A., the L.A. group that instantly put him in the upper echelon of lyricists and rappers, Ice Cube spent some time in New York, holed up in the studio space of production team the Bomb Squad. He went through their voluminous record collection looking for inspiration and what would become the sound of his first solo album. What they landed on was an album that carried the same density as the Squad’s other famous collaborators Public Enemy but was much more funky. The feel of the beats loosened Cube’s tongue considerably. He remained true to the storytelling vibe he established on Straight Outta Compton with his clear-eyed perspective on life in South Central L.A. but developed a leaner pugnaciousness that helped fuel the war on words with his former partners and cut down to size the fools that dared to question his skills and strength. —Robert Ham

292. David Bowie: Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps) (1980)

Few artists held court over rock ‘n’ roll quite like David Bowie did between 1971 and 1980. Starting his reign with Hunky Dory, the Thin White Duke dropped a run of 11 albums that, when it was all said and done, stand alone in the canon of popular music. You could go Heroes or Station to Station here, sure, but there’s something particularly perfect about Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps), the perfect merger of glam rock and disco. “Ashes to Ashes” calls back to Major Tom, while “Fashion” blurs the line between trends in music and clothes. Bowie here is at the forefront of his clubbiest self, and the title-track is a perfect mirage of metallic, sleazy, post-punk debauchery. Time and time again, when I return to Scary Monsters, it is to check in with “Teenage Wildlife,” the track that has long flown under the radar of Bowie’s career but might just be the most anthemic piece of his chameleonic, influential puzzle—the same old thing in brand new drag. —Matt Mitchell

Few artists held court over rock ‘n’ roll quite like David Bowie did between 1971 and 1980. Starting his reign with Hunky Dory, the Thin White Duke dropped a run of 11 albums that, when it was all said and done, stand alone in the canon of popular music. You could go Heroes or Station to Station here, sure, but there’s something particularly perfect about Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps), the perfect merger of glam rock and disco. “Ashes to Ashes” calls back to Major Tom, while “Fashion” blurs the line between trends in music and clothes. Bowie here is at the forefront of his clubbiest self, and the title-track is a perfect mirage of metallic, sleazy, post-punk debauchery. Time and time again, when I return to Scary Monsters, it is to check in with “Teenage Wildlife,” the track that has long flown under the radar of Bowie’s career but might just be the most anthemic piece of his chameleonic, influential puzzle—the same old thing in brand new drag. —Matt Mitchell

291. Camarón: La leyenda del tiempo (1979)

Camarón de la Isla is one of the greatest flamenco singers of all time, and his 10th album—La leyenda del tiempo—is his best and most polarizing work. The record saw Camarón making a departure from the traditional flamenco styles that had become definitive of Spain’s music scene, and the work alienated the genre’s purists and wound up culminating into a commercial failure (despite its critical acclaim). Now, we can look back at La leyenda del tiempo as the key example of flamenco’s sea change—as the genre was never the same before or after, all thanks to songs like the rumba of “Volando Voy” and the otherworldly-good title-track that catalyzes the album’s forward-momentum. Camarón’s voice here is one-of-a-kind, and the dual flamenco guitars from Tomatito and Raimundo Amador are some of the best guitar work on an album ever. —Matt Mitchell

Camarón de la Isla is one of the greatest flamenco singers of all time, and his 10th album—La leyenda del tiempo—is his best and most polarizing work. The record saw Camarón making a departure from the traditional flamenco styles that had become definitive of Spain’s music scene, and the work alienated the genre’s purists and wound up culminating into a commercial failure (despite its critical acclaim). Now, we can look back at La leyenda del tiempo as the key example of flamenco’s sea change—as the genre was never the same before or after, all thanks to songs like the rumba of “Volando Voy” and the otherworldly-good title-track that catalyzes the album’s forward-momentum. Camarón’s voice here is one-of-a-kind, and the dual flamenco guitars from Tomatito and Raimundo Amador are some of the best guitar work on an album ever. —Matt Mitchell

290. The Fall: The Wonderful and Frightening World Of… (1984)

Addictively repetitive melodies, the banging of not one, but two drummers, Mark E. Smith’s signature vocal snarl and a world of garagey post-punk experimentation go into one freaky, fun The Fall album. This, the band’s seventh of an impressive 31-studio album roster, showcases some real bits of discordant wonderful-and-frightening tunes, like “Disney’s Dream Debased,” “Elves,” “C.R.E.E.P.” and “Oh! Brother”—a slew of punky, political touchpoints which still feel relevant four decades later. The Wonderful and Frightening World Of The Fall captures the influential post-punk band in a solid, shining moment of scuzzy excellence. —Annie Nickoloff

Addictively repetitive melodies, the banging of not one, but two drummers, Mark E. Smith’s signature vocal snarl and a world of garagey post-punk experimentation go into one freaky, fun The Fall album. This, the band’s seventh of an impressive 31-studio album roster, showcases some real bits of discordant wonderful-and-frightening tunes, like “Disney’s Dream Debased,” “Elves,” “C.R.E.E.P.” and “Oh! Brother”—a slew of punky, political touchpoints which still feel relevant four decades later. The Wonderful and Frightening World Of The Fall captures the influential post-punk band in a solid, shining moment of scuzzy excellence. —Annie Nickoloff

289. Britney Spears: …Baby One More Time (1999)

We all know it. The pigtails. The mini skirt. The complete schoolgirl fantasy. However, when a 16-year-old future pop phenomenon grabbed that narrative and made it her own, the mainstream musical landscape was altered forever. A star straight from the crib, Spears spent her entire childhood crafting a persona fit for a pop princess performing in the Mickey Mouse Club, appearing in Broadway shows and even on Star Search. It was practically written in the stars that she was destined to become a megastar, and she proved it on …Baby One More Time. With her distinctive mellowed-out sexy vocals and unstoppable presence, the album’s lead single, “…Baby One More Time,” blasted her to international success. While it’s impossible to compare the caliber of the other tracks to such a mega-hit, the dial-up pop ballad “Sometimes” and the bubblegum pop fantasy “(You Drive Me) Crazy” proved that Spears’s vocal ability was one to be reckoned with. —Olivia Abercrombie

We all know it. The pigtails. The mini skirt. The complete schoolgirl fantasy. However, when a 16-year-old future pop phenomenon grabbed that narrative and made it her own, the mainstream musical landscape was altered forever. A star straight from the crib, Spears spent her entire childhood crafting a persona fit for a pop princess performing in the Mickey Mouse Club, appearing in Broadway shows and even on Star Search. It was practically written in the stars that she was destined to become a megastar, and she proved it on …Baby One More Time. With her distinctive mellowed-out sexy vocals and unstoppable presence, the album’s lead single, “…Baby One More Time,” blasted her to international success. While it’s impossible to compare the caliber of the other tracks to such a mega-hit, the dial-up pop ballad “Sometimes” and the bubblegum pop fantasy “(You Drive Me) Crazy” proved that Spears’s vocal ability was one to be reckoned with. —Olivia Abercrombie

288. The Who: Tommy (1969)

To borrow slightly from Tommy’s “Overture,” Captain Walker never came home, and he’ll never know that his (fictional) absence helped spawn one of rock’s most epic narratives. To follow The Who Sell Out, the British band devoted 24 tracks and 74 minutes to unraveling the fraught life of one pinball wizard, Tommy Walker. Bursts of acoustic suspense and hard rock rapture on songs like “Sparks” and “I’m Free” demonstrate the band’s approach to sound-driven storytelling, as they hone the vibrations that their “deaf, dumb and blind” titular character largely relies on to understand the world. “When you listen to the music you can actually become aware of the boy, and aware of what he is all about, because we are creating him as we play,” guitarist Pete Townshend reflected, an approach that has resulted in Tommy doubling as the quintessential rock opera, and to many fans, the quintessential record from The Who. —Victoria Wasylak

To borrow slightly from Tommy’s “Overture,” Captain Walker never came home, and he’ll never know that his (fictional) absence helped spawn one of rock’s most epic narratives. To follow The Who Sell Out, the British band devoted 24 tracks and 74 minutes to unraveling the fraught life of one pinball wizard, Tommy Walker. Bursts of acoustic suspense and hard rock rapture on songs like “Sparks” and “I’m Free” demonstrate the band’s approach to sound-driven storytelling, as they hone the vibrations that their “deaf, dumb and blind” titular character largely relies on to understand the world. “When you listen to the music you can actually become aware of the boy, and aware of what he is all about, because we are creating him as we play,” guitarist Pete Townshend reflected, an approach that has resulted in Tommy doubling as the quintessential rock opera, and to many fans, the quintessential record from The Who. —Victoria Wasylak

287. Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy: I See a Darkness (1999)

Love and loss. Hope and fear. Dreams and dread. Death, death and more death. These are the themes that ripple through I See A Darkness, Will Oldham’s sixth full-length album but first as Bonnie “Prince” Billy, a name he has used ever since. Perhaps it is no coincidence, then, that this is where the Kentuckian’s eccentric vision comes into sharp focus: Appalachian-inspired country-folk, existential musings, vivid storytelling, strange phrasing and a pervasive sense of unease. These are timeless songs that keep you on your toes. —Ben Salmon

Love and loss. Hope and fear. Dreams and dread. Death, death and more death. These are the themes that ripple through I See A Darkness, Will Oldham’s sixth full-length album but first as Bonnie “Prince” Billy, a name he has used ever since. Perhaps it is no coincidence, then, that this is where the Kentuckian’s eccentric vision comes into sharp focus: Appalachian-inspired country-folk, existential musings, vivid storytelling, strange phrasing and a pervasive sense of unease. These are timeless songs that keep you on your toes. —Ben Salmon

286. The KLF: Chill Out (1990)

While largely a thing of the past, every great party used to have a chill-out room—a space for overwhelmed ravers to decompress as night trudged into morning. UK duo The KLF spent most of their career putting out blocky acid house bangers. But their third album, 1990’s Chill Out, is an uncharacteristically atmospheric detour. Intended as a balm for clubbers on the come down, the record uses clattering samples, stabby synths and lonesome slide guitar swells to portray a journey through the American Gulf Coast states. On top of being an interesting relic from a formatively hedonistic moment in underground culture, the interconnected tracks are downright stunning. The whole thing captures the energy of watching the sunrise over a muddy field, dissociated from the constraints of societal convention. —Ted Davis

While largely a thing of the past, every great party used to have a chill-out room—a space for overwhelmed ravers to decompress as night trudged into morning. UK duo The KLF spent most of their career putting out blocky acid house bangers. But their third album, 1990’s Chill Out, is an uncharacteristically atmospheric detour. Intended as a balm for clubbers on the come down, the record uses clattering samples, stabby synths and lonesome slide guitar swells to portray a journey through the American Gulf Coast states. On top of being an interesting relic from a formatively hedonistic moment in underground culture, the interconnected tracks are downright stunning. The whole thing captures the energy of watching the sunrise over a muddy field, dissociated from the constraints of societal convention. —Ted Davis

285. Lil’ Kim: Hard Core (1996)

Lil’ Kim’s finest fashion moment was not when Diana Ross jiggled her purple-pasty-clad breast at the 1999 MTV Video Music Awards, nor was it the photoshoot where she snapped into an iconic squat wearing little more than a leopard print bikini. Instead, it’s one of the first lyrics on her album Hard Core, demanding one org*sm per carat in her diamond rings. “That’s how many times I wanna come / 21 / And another one, and another one,” she begins to boast on “Big Momma Thang,” the Jay-Z collab from her raunchy solo debut. Lil’ Kim’s ravenous libido and no-nonsense attitude penetrate every aspect of Hard Core—as she assumes the role of self-appointed rap royalty, her first decree being to refocus the public’s perception of women’s sexuality. When she flipped the Notorious B.I.G.’s objectifying tune “Just Playing (Dreams)” on its head with “Dreams,” her own equally-sexed-up take, Hard Core asserted that it’s not just on par with the hip-hop greats—it is one of the greats, and remains so to this day. —Victoria Wasylak

Lil’ Kim’s finest fashion moment was not when Diana Ross jiggled her purple-pasty-clad breast at the 1999 MTV Video Music Awards, nor was it the photoshoot where she snapped into an iconic squat wearing little more than a leopard print bikini. Instead, it’s one of the first lyrics on her album Hard Core, demanding one org*sm per carat in her diamond rings. “That’s how many times I wanna come / 21 / And another one, and another one,” she begins to boast on “Big Momma Thang,” the Jay-Z collab from her raunchy solo debut. Lil’ Kim’s ravenous libido and no-nonsense attitude penetrate every aspect of Hard Core—as she assumes the role of self-appointed rap royalty, her first decree being to refocus the public’s perception of women’s sexuality. When she flipped the Notorious B.I.G.’s objectifying tune “Just Playing (Dreams)” on its head with “Dreams,” her own equally-sexed-up take, Hard Core asserted that it’s not just on par with the hip-hop greats—it is one of the greats, and remains so to this day. —Victoria Wasylak

284. Talk Talk: Laughing Stock (1991)

If you know anything about Talk Talk as a casual fan, it might be the confounding trajectory of their five albums—from the slow progression from the New Romantic-aligned synth-pop of their 1982 debut The Party’s Over to the complex, pastoral post-rock of final two albums Spirit of Eden and Laughing Stock. With the latter, lead singer and songwriter Mark Hollis arguably crafted his masterpiece, recording his atmospheric, jazz-tinged hymns entirely in the dark and ruminating on sin, divine wrath and redemption. Even in its dramatic existentialism or perhaps less accessible structure, Laughing Stock prevails as one of the most important albums of all time because of the way it expresses that which is singularly human—both in the fear of the unknown and the beauty which sustains us in the meantime. —Elise Soutar

If you know anything about Talk Talk as a casual fan, it might be the confounding trajectory of their five albums—from the slow progression from the New Romantic-aligned synth-pop of their 1982 debut The Party’s Over to the complex, pastoral post-rock of final two albums Spirit of Eden and Laughing Stock. With the latter, lead singer and songwriter Mark Hollis arguably crafted his masterpiece, recording his atmospheric, jazz-tinged hymns entirely in the dark and ruminating on sin, divine wrath and redemption. Even in its dramatic existentialism or perhaps less accessible structure, Laughing Stock prevails as one of the most important albums of all time because of the way it expresses that which is singularly human—both in the fear of the unknown and the beauty which sustains us in the meantime. —Elise Soutar

283. Bob Marley and the Wailers: Burnin’ (1973)

For listeners who may only know Bob Marley’s musis through the ubiquitous Legend compilation, a true misconception would be that his music is colored by a sunny, positive, outlook on the world. The truth is, Marley, much like Curtis Mayfield or Fela Kuti, wrote as much about his anger towards the injustices being committed against his people in Jamaica and the oppressed around the globe as he did about the redemptive powers of love. On their sixth album Burnin’—the last true album as the Wailers since founding members Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer would leave the group shortly after its release—Marley and the group offer their fiercest calls to action up until that point. The most recognizable tunes here are the immortal anti-authority anthems “Get Up, Stand Up” and “I Shot The Sheriff.” But perhaps the album’s hidden thesis statement is it’s closing track, the seething “Burnin’ and Lootin’.” The song takes the positive outlook of his peer Jimmy Cliff’s “Many Rivers To Cross” and calls out how futile the kumbaya approach towards militarized police aggression truly is. “How many rivers do we have to cross before we can talk to the boss,” he asks with an inflection so palpably frustrated you can envision his tightly clenched fist in the vocal booth. Evil and oppressive forces only listen to strong action. Marley knows this and that’s why his call for not only “burnin’ and lootin’” but burning “all illusion” of a society that works for all remains as powerful as ever today. —Pat King

For listeners who may only know Bob Marley’s musis through the ubiquitous Legend compilation, a true misconception would be that his music is colored by a sunny, positive, outlook on the world. The truth is, Marley, much like Curtis Mayfield or Fela Kuti, wrote as much about his anger towards the injustices being committed against his people in Jamaica and the oppressed around the globe as he did about the redemptive powers of love. On their sixth album Burnin’—the last true album as the Wailers since founding members Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer would leave the group shortly after its release—Marley and the group offer their fiercest calls to action up until that point. The most recognizable tunes here are the immortal anti-authority anthems “Get Up, Stand Up” and “I Shot The Sheriff.” But perhaps the album’s hidden thesis statement is it’s closing track, the seething “Burnin’ and Lootin’.” The song takes the positive outlook of his peer Jimmy Cliff’s “Many Rivers To Cross” and calls out how futile the kumbaya approach towards militarized police aggression truly is. “How many rivers do we have to cross before we can talk to the boss,” he asks with an inflection so palpably frustrated you can envision his tightly clenched fist in the vocal booth. Evil and oppressive forces only listen to strong action. Marley knows this and that’s why his call for not only “burnin’ and lootin’” but burning “all illusion” of a society that works for all remains as powerful as ever today. —Pat King

282. Brian Eno: Another Green World (1975)

Brian Eno’s third solo album is the bridge between his rock beginnings and his ambient trailblazing. On Another Green World, Eno builds warm textures through organ and piano, synthesizers and noise generators, early drum machines, Robert Fripp’s extraterrestrial guitar leads, and even a couple of drum performances by Phil Collins. It’s definitely more minimal than his first two LPs, but it’s far from Music from Airports; there’s still singing on five of its 14 songs, most notably on the beautiful (and oft-covered) pop song “St. Elmo’s Fire” and the swaying trot of “I’ll Come Running,” and instrumentals like “The Big Ship” and “Sombre Reptiles” explore rhythms, melodies, and emotions in structures not too far removed from more conventional pop music. It’s clearly a transitional work that combines the best of Eno’s early era with some of the techniques and ambitions that would come to define him; the songs with vocals are more abstract and experimental than what he accomplished on Here Come the Warm Jets and Taking Tiger Mountain, and you can hear the seeds of Eno’s later work throughout. All in all it’s a foundational classic from a weird era when the mainstream rock world and major labels still had a bit of room for groundbreaking experimentalists. —Garrett Martin

Brian Eno’s third solo album is the bridge between his rock beginnings and his ambient trailblazing. On Another Green World, Eno builds warm textures through organ and piano, synthesizers and noise generators, early drum machines, Robert Fripp’s extraterrestrial guitar leads, and even a couple of drum performances by Phil Collins. It’s definitely more minimal than his first two LPs, but it’s far from Music from Airports; there’s still singing on five of its 14 songs, most notably on the beautiful (and oft-covered) pop song “St. Elmo’s Fire” and the swaying trot of “I’ll Come Running,” and instrumentals like “The Big Ship” and “Sombre Reptiles” explore rhythms, melodies, and emotions in structures not too far removed from more conventional pop music. It’s clearly a transitional work that combines the best of Eno’s early era with some of the techniques and ambitions that would come to define him; the songs with vocals are more abstract and experimental than what he accomplished on Here Come the Warm Jets and Taking Tiger Mountain, and you can hear the seeds of Eno’s later work throughout. All in all it’s a foundational classic from a weird era when the mainstream rock world and major labels still had a bit of room for groundbreaking experimentalists. —Garrett Martin

281. Shin Joong Hyun & Yup Juns: 신중현과 엽전들 (1974)

The self-titled debut album from Shin Joong Hyun & Yup Juns is one of the greatest documents of psych- and blues-rock to ever exist, running circles around what many of their American contemporaries had done the decade prior. The three-piece, led by guitarist and vocalist Shin Jung-hyeon, drummer Kim Ho-Sik and bassist Lee Nam-yi, only lasted three years—destroyed over time by South Korea’s government, who arrested Shin Jung-hyeon for marijuana use in 1972 and committed him to a mental institution for treatment. After years of censorship, the Ministry of Culture and Public Information banned 54 artists from releasing albums and playing in public in 1976, including Shin—leading to the Yup Juns’ disbandment. The Yup Juns’ song “The Beauty” was banned under Park Chung-hee’s dictatorship, but tracks like “Think” and “Anticipation” are such perfect old-school rhythm and blues gems that merge elements of swamp and roots. The Yup Juns remain one of the greatest South Korean groups to ever exist, and they were instrumental in helping integrate a harder, grittier rock ‘n’ roll into the tastes of their generation in Seoul. —Matt Mitchell

The self-titled debut album from Shin Joong Hyun & Yup Juns is one of the greatest documents of psych- and blues-rock to ever exist, running circles around what many of their American contemporaries had done the decade prior. The three-piece, led by guitarist and vocalist Shin Jung-hyeon, drummer Kim Ho-Sik and bassist Lee Nam-yi, only lasted three years—destroyed over time by South Korea’s government, who arrested Shin Jung-hyeon for marijuana use in 1972 and committed him to a mental institution for treatment. After years of censorship, the Ministry of Culture and Public Information banned 54 artists from releasing albums and playing in public in 1976, including Shin—leading to the Yup Juns’ disbandment. The Yup Juns’ song “The Beauty” was banned under Park Chung-hee’s dictatorship, but tracks like “Think” and “Anticipation” are such perfect old-school rhythm and blues gems that merge elements of swamp and roots. The Yup Juns remain one of the greatest South Korean groups to ever exist, and they were instrumental in helping integrate a harder, grittier rock ‘n’ roll into the tastes of their generation in Seoul. —Matt Mitchell

280. Townes Van Zandt: The Late Great Townes Van Zandt (1972)

Townes Van Zandt isn’t exactly what you would call an “album artist.” A perpetual vagabond and often at the end of his rope, Van Zandt’s albums are often messy and haphazard. And yet, when you are able to cobble together an album featuring two of the greatest country-folk songs of all time, you make a great case for yourself on a list like this. “Pancho and Lefty” and “If I Needed You” are wonderful encapsulations of Townes as a songwriter and a storyteller, one for whom existential loneliness is often the lingua franca. The latter may be about a girl, the former about life on the road, but both are about leaving and what gets left behind—universal notions Van Zandt always spun into utter masterpieces. —Sean Fennell

Townes Van Zandt isn’t exactly what you would call an “album artist.” A perpetual vagabond and often at the end of his rope, Van Zandt’s albums are often messy and haphazard. And yet, when you are able to cobble together an album featuring two of the greatest country-folk songs of all time, you make a great case for yourself on a list like this. “Pancho and Lefty” and “If I Needed You” are wonderful encapsulations of Townes as a songwriter and a storyteller, one for whom existential loneliness is often the lingua franca. The latter may be about a girl, the former about life on the road, but both are about leaving and what gets left behind—universal notions Van Zandt always spun into utter masterpieces. —Sean Fennell

279. Robyn: Body Talk (2010)

No pop singer/songwriter in the last 20 years has made as much monumental dance music as Robyn has. The Swedish singer is as close to a one-in-a-million star as anyone else on this list, but her album, Body Talk is one of the best synth-pop projects ever. Though you might consider it to be a compilation album, it’s still a studio work that combines all of the tracks from her two-part Body Talk series—and both entries deserve some spotlight. Spearheaded by the monster single “Dancing On My Own,” it’s here, in 2010, where Robyn found her own immortality. Pulling influence from Prince’s Dirty Mind, the Knife’s Silent Shout and Kate Bush’s The Kick Inside, she made a dance record that is still, 13 years later, a club fixture. “Fembot,” “Dancehall Queen” and “Hang with Me” are each perfect on their own accord and help propel Body Talk into the echelons of electronic music forever. —Matt Mitchell

No pop singer/songwriter in the last 20 years has made as much monumental dance music as Robyn has. The Swedish singer is as close to a one-in-a-million star as anyone else on this list, but her album, Body Talk is one of the best synth-pop projects ever. Though you might consider it to be a compilation album, it’s still a studio work that combines all of the tracks from her two-part Body Talk series—and both entries deserve some spotlight. Spearheaded by the monster single “Dancing On My Own,” it’s here, in 2010, where Robyn found her own immortality. Pulling influence from Prince’s Dirty Mind, the Knife’s Silent Shout and Kate Bush’s The Kick Inside, she made a dance record that is still, 13 years later, a club fixture. “Fembot,” “Dancehall Queen” and “Hang with Me” are each perfect on their own accord and help propel Body Talk into the echelons of electronic music forever. —Matt Mitchell

278. Hiroshi Yoshimura: Music For Nine Post Cards (1982)

On his 1982 debut, Music For Nine Post Cards, Hiroshi Yoshimura burst into the world with a daylit, dreamy formula. The Japanese producer self-recorded the album using a Fender Rhodes, sonically aiming to evoke seasonal changes in a small town. But until a 2017 reissue via the label Empire of Signs, Yoshimura remained unjustly overlooked on an international scale. The posthumous re-release transformed him into a giant on streaming platforms, acting as a mesmerizing gateway for listeners just starting to dabble with wordless music. Music For Nine Post Cards is not just the quintessential Japanese ambient album, it’s the most earnest and pure New Age record of all time. —Ted Davis

On his 1982 debut, Music For Nine Post Cards, Hiroshi Yoshimura burst into the world with a daylit, dreamy formula. The Japanese producer self-recorded the album using a Fender Rhodes, sonically aiming to evoke seasonal changes in a small town. But until a 2017 reissue via the label Empire of Signs, Yoshimura remained unjustly overlooked on an international scale. The posthumous re-release transformed him into a giant on streaming platforms, acting as a mesmerizing gateway for listeners just starting to dabble with wordless music. Music For Nine Post Cards is not just the quintessential Japanese ambient album, it’s the most earnest and pure New Age record of all time. —Ted Davis

277. Pulp: Different Class (1995)

If 1994’s His N’ Hers was Pulp’s first foray into the mainstream consciousness, then Different Class was the album that made sure that Jarvis co*cker and his band would remain pop culture figures for years to come. The band’s most successful single, “Common People,” was an anthem that continued the band’s dedication towards exploring ‘90s Britain from a working-class perspective, with its narrative of class divide and poverty tourism still ringing true to this day. Different Class exemplified all the best aspects of co*ckers’ lens into the homes of everyday people as he explored horniness, fractured relationships and dreams of stardom. Pulp were proudly flying the flag for those who saw themselves as outsiders. —Matty Pywell

If 1994’s His N’ Hers was Pulp’s first foray into the mainstream consciousness, then Different Class was the album that made sure that Jarvis co*cker and his band would remain pop culture figures for years to come. The band’s most successful single, “Common People,” was an anthem that continued the band’s dedication towards exploring ‘90s Britain from a working-class perspective, with its narrative of class divide and poverty tourism still ringing true to this day. Different Class exemplified all the best aspects of co*ckers’ lens into the homes of everyday people as he explored horniness, fractured relationships and dreams of stardom. Pulp were proudly flying the flag for those who saw themselves as outsiders. —Matty Pywell

276. Vampire Weekend: Modern Vampires of the City (2013)

Vampire Weekend emerged in the late 2000s as one of indie rock’s coolest and most distinctive bands. With two critically acclaimed records under their belt by the time 2013 hit, the hype for the intellectual millennial outfit’s third record was so immense that someone had infamously fabricated a cover for it and titled it Lemon Sounds. Luckily, 2013’s Modern Vampires of the City, their actual third album, would effectively defy the preppy-twee mold that people began boxing Vampire Weekend into. Where their charming 2008 self-titled debut and their giddy 2010 follow-up Contra were home runs, Modern Vampires of the City felt like a grand slam, somehow both playful and precise in its experimentation with pitch-shifting (“Diane Young,” “Ya Hey”), hyper-speed vocals (“Worship You”) and dense wordplay (“Step”). Producer Ariel Rechtstaid and former band member Rostam Batmanglij were especially integral to shaping the album’s haunted quality, giving a chilly yet vibrant life to frontman Ezra Koenig’s poetic musings about faith and mortality. —Sam Rosenberg

Vampire Weekend emerged in the late 2000s as one of indie rock’s coolest and most distinctive bands. With two critically acclaimed records under their belt by the time 2013 hit, the hype for the intellectual millennial outfit’s third record was so immense that someone had infamously fabricated a cover for it and titled it Lemon Sounds. Luckily, 2013’s Modern Vampires of the City, their actual third album, would effectively defy the preppy-twee mold that people began boxing Vampire Weekend into. Where their charming 2008 self-titled debut and their giddy 2010 follow-up Contra were home runs, Modern Vampires of the City felt like a grand slam, somehow both playful and precise in its experimentation with pitch-shifting (“Diane Young,” “Ya Hey”), hyper-speed vocals (“Worship You”) and dense wordplay (“Step”). Producer Ariel Rechtstaid and former band member Rostam Batmanglij were especially integral to shaping the album’s haunted quality, giving a chilly yet vibrant life to frontman Ezra Koenig’s poetic musings about faith and mortality. —Sam Rosenberg

275. Kraftwerk: The Man-Machine (1978)

German quartet Kraftwerk have about five albums that could’ve fit into this slot, but we’ve opted to move forward with The Man-Machine—the band’s 1978 masterpiece that is, at its core, the godfather of synth-pop as we know it. It’s here where Kraftwerk took their mechanical style of old and re-tuned it into a club-worthy aesthetic. The album is a beautiful example of early-era electro-pop architecture, and it laid the groundwork for what bands like Depeche Mode, OMD and Pet Shop Boys would aim to do in the decade that followed. Centerpiece “The Model” feels as brand-new now as it did 45 years ago, while songs like “Neon Lights,” “Metropolis” and “The Robots” all signal early installments of the cybernetic dance-pop that would flood the charts at the turn of 1981. Like always, Kraftwerk were ahead of the curve. Although, you could argue that—on The Man-Machine—they invented the curve altogether. —Matt Mitchell

German quartet Kraftwerk have about five albums that could’ve fit into this slot, but we’ve opted to move forward with The Man-Machine—the band’s 1978 masterpiece that is, at its core, the godfather of synth-pop as we know it. It’s here where Kraftwerk took their mechanical style of old and re-tuned it into a club-worthy aesthetic. The album is a beautiful example of early-era electro-pop architecture, and it laid the groundwork for what bands like Depeche Mode, OMD and Pet Shop Boys would aim to do in the decade that followed. Centerpiece “The Model” feels as brand-new now as it did 45 years ago, while songs like “Neon Lights,” “Metropolis” and “The Robots” all signal early installments of the cybernetic dance-pop that would flood the charts at the turn of 1981. Like always, Kraftwerk were ahead of the curve. Although, you could argue that—on The Man-Machine—they invented the curve altogether. —Matt Mitchell

274. Songs: Ohia: The Magnolia Electric Co. (2003)

After releasing a series of excellent, oft-bleak lo-fi indie-rock albums in the late ‘90s and early 2000s, Jason Molina expanded his ambitions with 2003’s The Magnolia Electric Co.—a rocking Americana epic that paired intimate musings with an expansive soundscape. Over two decades later, the LP remains Molina’s most incisive, offering a devastatingly unfiltered look into a beautiful tortured soul. “Everything you hated me for / Honey there was so much more / I just didn’t get busted,” he opined on the devastating “Just Be Simple” 10 years before his demons would eventually catch up to him. But on Magnolia Electric Co., Molina was more than just a tragic figure; he was a brave troubadour unafraid to shy away from all the beauty and tragedy of life. On the bittersweet closer “Hold On Magnolia,” he stared down the abyss and held on to the “last light” he saw. In doing so, he created torch songs for the bruised and battered among us. —Tom Williams

After releasing a series of excellent, oft-bleak lo-fi indie-rock albums in the late ‘90s and early 2000s, Jason Molina expanded his ambitions with 2003’s The Magnolia Electric Co.—a rocking Americana epic that paired intimate musings with an expansive soundscape. Over two decades later, the LP remains Molina’s most incisive, offering a devastatingly unfiltered look into a beautiful tortured soul. “Everything you hated me for / Honey there was so much more / I just didn’t get busted,” he opined on the devastating “Just Be Simple” 10 years before his demons would eventually catch up to him. But on Magnolia Electric Co., Molina was more than just a tragic figure; he was a brave troubadour unafraid to shy away from all the beauty and tragedy of life. On the bittersweet closer “Hold On Magnolia,” he stared down the abyss and held on to the “last light” he saw. In doing so, he created torch songs for the bruised and battered among us. —Tom Williams

273. Neil Young: After the Gold Rush (1970)

Along with Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks, After the Gold Rush is one of the greatest break-up records ever made regardless of intention. Even though it has nothing to do with the album, which was inspired by a Dean Stockwell-Herb Berman screenplay, I liked to imagine that it was written to capture the feeling too often ignored by movies and music. Songs like “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” and “When You Dance I Can Really Love” charted, while songs like “Tell Me Why,” “I Believe in You” and “Don’t Let It Bring You Down” became fixtures in Neil Young’s sets for years after After the Gold Rush’s release. The 11 songs embrace the truth of loss that comes after the magic, after the bum-rush of serotonin and possibilities, after you realize the holes inside haven’t been plugged, that the overflow of emotion you poured in ran right out. —Jeff Gonick

Along with Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks, After the Gold Rush is one of the greatest break-up records ever made regardless of intention. Even though it has nothing to do with the album, which was inspired by a Dean Stockwell-Herb Berman screenplay, I liked to imagine that it was written to capture the feeling too often ignored by movies and music. Songs like “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” and “When You Dance I Can Really Love” charted, while songs like “Tell Me Why,” “I Believe in You” and “Don’t Let It Bring You Down” became fixtures in Neil Young’s sets for years after After the Gold Rush’s release. The 11 songs embrace the truth of loss that comes after the magic, after the bum-rush of serotonin and possibilities, after you realize the holes inside haven’t been plugged, that the overflow of emotion you poured in ran right out. —Jeff Gonick

272. Blondie: Parallel Lines (1978)

As a fellow blond, Debbie Harry has always been an idol of mine, and her badass personality just adds to the adoration. After bursting onto the New York music scene with their punk-centric, self-titled debut—followed up by the rowdy Plastic Letters—fans got a taste of what silkier new wave hooks would come on their third album, Parallel Lines. “Heart Of Glass” is an enduring Blondie classic for its funky guitar grooves and Harry’s biting lyricism of a toxic romance—the theme song for many a scorned lover. Though “Heart Of Glass” and the taunting roar of “One Way Or Another” are the most recognizable tracks, the rest of Parallel Lines boasts Blondie’s unmistakable flavor of intoxicating post-punk. The doo-wop-inspired “Pretty Baby” is infectiously catchy, and the CBGB icons brought groovy psychedelia to the front of the line with “Fade Away And Radiate” (with a guest appearance from Robert Fripp of King Crimson on a wailing guitar solo). Blondie’s Parallel Lines solidified the band as pioneers of a beloved musical movement.. —Olivia Abercrombie

As a fellow blond, Debbie Harry has always been an idol of mine, and her badass personality just adds to the adoration. After bursting onto the New York music scene with their punk-centric, self-titled debut—followed up by the rowdy Plastic Letters—fans got a taste of what silkier new wave hooks would come on their third album, Parallel Lines. “Heart Of Glass” is an enduring Blondie classic for its funky guitar grooves and Harry’s biting lyricism of a toxic romance—the theme song for many a scorned lover. Though “Heart Of Glass” and the taunting roar of “One Way Or Another” are the most recognizable tracks, the rest of Parallel Lines boasts Blondie’s unmistakable flavor of intoxicating post-punk. The doo-wop-inspired “Pretty Baby” is infectiously catchy, and the CBGB icons brought groovy psychedelia to the front of the line with “Fade Away And Radiate” (with a guest appearance from Robert Fripp of King Crimson on a wailing guitar solo). Blondie’s Parallel Lines solidified the band as pioneers of a beloved musical movement.. —Olivia Abercrombie

271. Wire: Chairs Missing (1978)

The art school punk provocateurs in Wire put out three albums during their initial phase, and all three are classics that sound very different from each other. Chairs Missing, their second LP, is the best of the bunch, and one of the most important albums ever recorded. It’s hard to imagine “post-punk” even existing as a genre tag without this record; although a couple of songs recall the minimal, straight-forward punk of 1977’s Pink Flag, the rest of the album adds synthesizers, guitar effects, a disco beat on “Another the Letter,” and various other flourishes and experiments that clearly marked this as something new and different at the time. It foreshadowed so much of the punk-derived music that followed that you can draw a straight line from Chairs Missing to a handful of different indie-rock subgenres. —Garrett Martin

The art school punk provocateurs in Wire put out three albums during their initial phase, and all three are classics that sound very different from each other. Chairs Missing, their second LP, is the best of the bunch, and one of the most important albums ever recorded. It’s hard to imagine “post-punk” even existing as a genre tag without this record; although a couple of songs recall the minimal, straight-forward punk of 1977’s Pink Flag, the rest of the album adds synthesizers, guitar effects, a disco beat on “Another the Letter,” and various other flourishes and experiments that clearly marked this as something new and different at the time. It foreshadowed so much of the punk-derived music that followed that you can draw a straight line from Chairs Missing to a handful of different indie-rock subgenres. —Garrett Martin

270. Mississippi John Hurt: Today! (1966)

While pickers like Muddy Waters, Robert Johnson and John Lee Hooker have endured as the most recognizable faces in the history of blues music, none of them made an album quite as soul-stirring as Mississippi John Hurt’s 1966 classic, Today! Recorded in 1964, Hurt compiled 12 songs—five of them traditional, the rest original compositions, including “I’m Satisfied” and “Coffee Blues”—completely rewrote his own success. Today! came after Vanguard Records “rediscovered” him, and his voice hadn’t missed a beat. There’s a soft-spoken warmth rippling from end to end, as Hurt doesn’t ever quite growl with the same gravelly haze employed by his contemporaries. There was no need, though, as the gentleness of Today! works beautifully with the mellow, heavy-hearted tunes of Hurt’s greatest effort. As far as folk revival albums are concerned, the one made by a bluesman might be the very best of them all. —Matt Mitchell

While pickers like Muddy Waters, Robert Johnson and John Lee Hooker have endured as the most recognizable faces in the history of blues music, none of them made an album quite as soul-stirring as Mississippi John Hurt’s 1966 classic, Today! Recorded in 1964, Hurt compiled 12 songs—five of them traditional, the rest original compositions, including “I’m Satisfied” and “Coffee Blues”—completely rewrote his own success. Today! came after Vanguard Records “rediscovered” him, and his voice hadn’t missed a beat. There’s a soft-spoken warmth rippling from end to end, as Hurt doesn’t ever quite growl with the same gravelly haze employed by his contemporaries. There was no need, though, as the gentleness of Today! works beautifully with the mellow, heavy-hearted tunes of Hurt’s greatest effort. As far as folk revival albums are concerned, the one made by a bluesman might be the very best of them all. —Matt Mitchell

269. Fiona Apple: When the Pawn Hits the Conflicts He Thinks Like a King What He Knows Throws the Blows When He Goes to the Fight and He’ll Win the Whole Thing ‘Fore He Enters the Ring There’s No Body to Batter When Your Mind Is Your Might So When You Go Solo, You Hold Your Own Hand and Remember That Depth Is the Greatest of Heights and If You Know Where You Stand, Then You Know Where to Land and If You Fall It Won’t Matter, Cuz You’ll Know That You’re Right (1999)

After SPIN wrote a bad cover story about Fiona Apple, she wrote a poem that wound up being the entire title of her second studio album, When the Pawn… The Washington Post declared it Apple’s version of Chumbawamba’s “Tubthumping,” but the art-rock starlet’s sophom*ore LP gave out far greater tongue-lashings than “I get knocked down, but I get up again.” Apple didn’t just get up, she grew taller than those who criticized her after Tidal came out three years earlier. Jon Brion’s production is the game-changer here, and the music was not just melodically more complex—her voice had been worn down into a soulful vessel for misery, the arrangements limping around her like they came from the rib of a wounded orchestra. This was the moment Fiona Apple became bigger than Alanis, bigger than Tori, bigger than Jewell, bigger than Garbage and bigger than Liz Phair. —Matt Mitchell

After SPIN wrote a bad cover story about Fiona Apple, she wrote a poem that wound up being the entire title of her second studio album, When the Pawn… The Washington Post declared it Apple’s version of Chumbawamba’s “Tubthumping,” but the art-rock starlet’s sophom*ore LP gave out far greater tongue-lashings than “I get knocked down, but I get up again.” Apple didn’t just get up, she grew taller than those who criticized her after Tidal came out three years earlier. Jon Brion’s production is the game-changer here, and the music was not just melodically more complex—her voice had been worn down into a soulful vessel for misery, the arrangements limping around her like they came from the rib of a wounded orchestra. This was the moment Fiona Apple became bigger than Alanis, bigger than Tori, bigger than Jewell, bigger than Garbage and bigger than Liz Phair. —Matt Mitchell

268. Tom Petty: Wildflowers (1994)

Unconfined, Tom Petty brought a whole lot of heart into the songs of Wildflowers. The album, Petty’s second solo record following two decades of recording with the Heartbreakers (though many of them are featured on it), stands as a glimmering standout of folk-rock brilliance in his discography—one he referred to as his pet project, a career highlight. The title track’s declaration, “you belong somewhere you feel free,” is a motto for the record’s creation, crafted with longtime bandmates and producer Rick Rubin during a period of pure musical clarity. —Annie Nickoloff

Unconfined, Tom Petty brought a whole lot of heart into the songs of Wildflowers. The album, Petty’s second solo record following two decades of recording with the Heartbreakers (though many of them are featured on it), stands as a glimmering standout of folk-rock brilliance in his discography—one he referred to as his pet project, a career highlight. The title track’s declaration, “you belong somewhere you feel free,” is a motto for the record’s creation, crafted with longtime bandmates and producer Rick Rubin during a period of pure musical clarity. —Annie Nickoloff

267. Dolly Parton: Coat of Many Colors (1971)

The narrative that Dolly Parton lays out on “Coat of Many Colors,” the title track of her eighth solo album, is among the most endearing she has ever penned. “My coat of many colors that my mama made for me / Made only from rags but I wore it so proudly,” Parton sings in the refrain, her distinct voice soaring with glee and gratitude. Like Dolly’s mother, the country lodestar possesses a gift for crafting something memorable with unassuming materials. Nowhere in her immense catalog is that more evident than on Coat of Many Colors, as Parton fashions her simple yet affecting vocals and acoustic guitar for a grander purpose: to tell stories that stay with us for decades. —Grant Sharples

The narrative that Dolly Parton lays out on “Coat of Many Colors,” the title track of her eighth solo album, is among the most endearing she has ever penned. “My coat of many colors that my mama made for me / Made only from rags but I wore it so proudly,” Parton sings in the refrain, her distinct voice soaring with glee and gratitude. Like Dolly’s mother, the country lodestar possesses a gift for crafting something memorable with unassuming materials. Nowhere in her immense catalog is that more evident than on Coat of Many Colors, as Parton fashions her simple yet affecting vocals and acoustic guitar for a grander purpose: to tell stories that stay with us for decades. —Grant Sharples

266. Mahmoud Ahmed: Éthiopiques, Vol. 7: Ere Mèla Mèla (1975)

The Éthiopiques series has gifted the world some of the greatest Ethiopian music to ever exist, including work from Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou, Mulatu Astatke and Tlahoun Gessesse. But it’s the series’ seventh volume that towers over the rest. Made in 1975 by singer Mahmoud Ahmed, the album blends touches of psych-soul with jazz and lounge singing to make one of the greatest East African fusion projects of all time. The organ-heavy R&B band behind Ahmed get their kicks on a truly global range of influences, evoking everything from James Brown-rambunctiousness to Spanish flamenco. It’s an epic album, galvanized by the silk-woven “Tezeta” and the booming groove of “Belomi Benna.” —Matt Mitchell

The Éthiopiques series has gifted the world some of the greatest Ethiopian music to ever exist, including work from Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou, Mulatu Astatke and Tlahoun Gessesse. But it’s the series’ seventh volume that towers over the rest. Made in 1975 by singer Mahmoud Ahmed, the album blends touches of psych-soul with jazz and lounge singing to make one of the greatest East African fusion projects of all time. The organ-heavy R&B band behind Ahmed get their kicks on a truly global range of influences, evoking everything from James Brown-rambunctiousness to Spanish flamenco. It’s an epic album, galvanized by the silk-woven “Tezeta” and the booming groove of “Belomi Benna.” —Matt Mitchell

265. Thin Lizzy: Jailbreak (1976)

By the time Thin Lizzy put out their sixth album in 1976, the Irish rockers had found their groove completely. Jailbreak wasn’t just a commercial breakthrough in the United States for Phil Lynott and his band; it was a colossal achievement of hard-nosed rock ‘n’ roll. The songs are surprisingly baroque, given just how disgusting those guitars from Scott Gorham and Brian Robertson sound, but Lynott’s whiskey-soaked refrains inspired by the blues and glam-rock, Thin Lizzy soared beyond expectations, turning in three of the greatest rock tracks of the era: “The Boys Are Back in Town,” “Jailbreak” and “Cowboy Song.” While “The Boys Are Back in Town” has become TouchTunes royalty, “Cowboy Song” remains one of the most epic songs of the 1970s (that final guitar solo will split your head clean down the middle if you’re not careful). Jailbreak is strange, cosmic and pilled with grit. —Matt Mitchell

By the time Thin Lizzy put out their sixth album in 1976, the Irish rockers had found their groove completely. Jailbreak wasn’t just a commercial breakthrough in the United States for Phil Lynott and his band; it was a colossal achievement of hard-nosed rock ‘n’ roll. The songs are surprisingly baroque, given just how disgusting those guitars from Scott Gorham and Brian Robertson sound, but Lynott’s whiskey-soaked refrains inspired by the blues and glam-rock, Thin Lizzy soared beyond expectations, turning in three of the greatest rock tracks of the era: “The Boys Are Back in Town,” “Jailbreak” and “Cowboy Song.” While “The Boys Are Back in Town” has become TouchTunes royalty, “Cowboy Song” remains one of the most epic songs of the 1970s (that final guitar solo will split your head clean down the middle if you’re not careful). Jailbreak is strange, cosmic and pilled with grit. —Matt Mitchell

264. Stars of the Lid: The Tired Sounds of Stars of the Lid (2001)

On their sixth album as Stars of the Lid, The Tired Sounds of, Brian McBride and Adam Wiltzie don’t just come across groggy: They seem to dwell in some sleep-induced otherworld, doused in heavenly light. While it might sound like the Texas duo were working around traditional synthesizer pads in the studio, the 19-track record was actually built on groundbreaking tones generated from processed string and woodwind instruments, peppered with occasional samples pulled from arthouse films. Extended drone pieces can sometimes have a tendency to become pleasant, yet ignorable background noise. But The Tired Sounds of proves that this isn’t always the case, with a capacity to be as entrancing as it is cloudy. —Ted Davis

On their sixth album as Stars of the Lid, The Tired Sounds of, Brian McBride and Adam Wiltzie don’t just come across groggy: They seem to dwell in some sleep-induced otherworld, doused in heavenly light. While it might sound like the Texas duo were working around traditional synthesizer pads in the studio, the 19-track record was actually built on groundbreaking tones generated from processed string and woodwind instruments, peppered with occasional samples pulled from arthouse films. Extended drone pieces can sometimes have a tendency to become pleasant, yet ignorable background noise. But The Tired Sounds of proves that this isn’t always the case, with a capacity to be as entrancing as it is cloudy. —Ted Davis

263. Alvvays: Blue Rev (2022)

Alvvays are masters of quality over quantity—they know what they have to say, and they waste no time getting to the point. The most recent release on this list, Blue Rev is a joyride of masterfully written jangle-pop tunes that were recorded in one sitting, with producer Shawn Everett filling in the gaps and fleshing out the texture of the record’s all-killer-no-filler 14 tracks. The group became Grammy underdogs with the standout single “Belinda Says,” which contains one of the best key changes of the last decade. The musical chemistry between every member of Alvvays soars through each track’s story, many of which are inspired by frontwoman Molly Rankin’s favorite books, lyrics and Go-Go’s member. Blue Rev is an album about identity and sense of self. Alvvays, who’ve never dropped an EP or a standalone single, act without flaw. —Leah Weinstein

Alvvays are masters of quality over quantity—they know what they have to say, and they waste no time getting to the point. The most recent release on this list, Blue Rev is a joyride of masterfully written jangle-pop tunes that were recorded in one sitting, with producer Shawn Everett filling in the gaps and fleshing out the texture of the record’s all-killer-no-filler 14 tracks. The group became Grammy underdogs with the standout single “Belinda Says,” which contains one of the best key changes of the last decade. The musical chemistry between every member of Alvvays soars through each track’s story, many of which are inspired by frontwoman Molly Rankin’s favorite books, lyrics and Go-Go’s member. Blue Rev is an album about identity and sense of self. Alvvays, who’ve never dropped an EP or a standalone single, act without flaw. —Leah Weinstein

262. Silver Jews: American Water (1998)

In the almost five years since his passing, David Berman has come to be known as something of a tragic figure—a reputation born out of both his suicide and his final album, Purple Mountains, which he released four weeks prior to his death. But Berman was far more multifaceted and harder to box in, something captured on his magnum opus with Silver Jews: American Water. Here, he found connection in isolation (“Honk If You’re Lonely”) and poetic insight into life’s banalities, like the color of the road (“Random Rules”). On closer “The Wild Kindness,” he found hope. “I’m gonna shine out in the wild kindness,” he declared triumphantly, a fitting mission statement from a painfully empathetic, ingenious songwriter whose music offered a lifeline to other wandering souls. —Tom Williams

In the almost five years since his passing, David Berman has come to be known as something of a tragic figure—a reputation born out of both his suicide and his final album, Purple Mountains, which he released four weeks prior to his death. But Berman was far more multifaceted and harder to box in, something captured on his magnum opus with Silver Jews: American Water. Here, he found connection in isolation (“Honk If You’re Lonely”) and poetic insight into life’s banalities, like the color of the road (“Random Rules”). On closer “The Wild Kindness,” he found hope. “I’m gonna shine out in the wild kindness,” he declared triumphantly, a fitting mission statement from a painfully empathetic, ingenious songwriter whose music offered a lifeline to other wandering souls. —Tom Williams

261. The Meters: Rejuvenation (1974)

Few American bands have deserved more flowers than the Meters, who came out of New Orleans and completely transformed funk music forever. They were a backing group for folks like Lee Dorsey and Dr. John over the years, and their work is, by far, a mark of origination. When Mick Jagger saw them play at the release party for Wings’ Venus and Mars, he asked them to open for the Rolling Stones from 1975-76. Few funk bands have ever done it like the Meters, and their 1974 album Rejuvenation is a marquee entry into the genre’s history. Part-funk and part-swamp rock, Rejuvenation lives up to its title, as songs like “Just Kissed My Baby” and “Hey Pocky A-Way” celebrate the co-lead vocalist triumphs of bandleaders Ziggy Modeliste and Art Neville while ushering the choral flourishes of female backing vocalists into the fray. The Meters have continuously been one of the most influential bands ever, and that much is true for Rejuvenation—as the Red Hot Chili Peppers covered “Africa,” Public Enemy sampled “Just Kissed My Baby” on their album Yo! Bum Rush the Show and the Grateful Dead often performed “Hey Pocky A-Way” in the late-1980s. Incorporating country, R&B, gospel and Mardi Gras rhythm into their sound, Rejuvenation is the Meters at a zenith. —Matt Mitchell

Few American bands have deserved more flowers than the Meters, who came out of New Orleans and completely transformed funk music forever. They were a backing group for folks like Lee Dorsey and Dr. John over the years, and their work is, by far, a mark of origination. When Mick Jagger saw them play at the release party for Wings’ Venus and Mars, he asked them to open for the Rolling Stones from 1975-76. Few funk bands have ever done it like the Meters, and their 1974 album Rejuvenation is a marquee entry into the genre’s history. Part-funk and part-swamp rock, Rejuvenation lives up to its title, as songs like “Just Kissed My Baby” and “Hey Pocky A-Way” celebrate the co-lead vocalist triumphs of bandleaders Ziggy Modeliste and Art Neville while ushering the choral flourishes of female backing vocalists into the fray. The Meters have continuously been one of the most influential bands ever, and that much is true for Rejuvenation—as the Red Hot Chili Peppers covered “Africa,” Public Enemy sampled “Just Kissed My Baby” on their album Yo! Bum Rush the Show and the Grateful Dead often performed “Hey Pocky A-Way” in the late-1980s. Incorporating country, R&B, gospel and Mardi Gras rhythm into their sound, Rejuvenation is the Meters at a zenith. —Matt Mitchell

260. PJ Harvey: Stories from the City, Stories from the Sea (2000)

Stories does defiance in a way she hadn’t yet explored, and feels confident in a way that floats above the rest of the world, rather than fighting back. What else in her discography captures the head-on swagger of something like “Big Exit” or “This is Love”? What else sounds like the gentle glide of Thom Yorke’s voice underpinning Polly’s in “Beautiful Feeling,” or the heavy, warm piano march that carries “Horses In My Dreams”? Even the gentle collapse and defeat of “We Float” feels like light flooding your senses in the best possible way. Though it’s unlikely that Polly will ever make anything this purposefully polished again, it’s a little blip of calm in the eye of the larger storm, a moment of shimmering assurance among a back catalog that largely aims to make the listener uncomfortable. Few albums by anyone have captured that precise feeling, making Stories something truly special. —Elise Soutar

Stories does defiance in a way she hadn’t yet explored, and feels confident in a way that floats above the rest of the world, rather than fighting back. What else in her discography captures the head-on swagger of something like “Big Exit” or “This is Love”? What else sounds like the gentle glide of Thom Yorke’s voice underpinning Polly’s in “Beautiful Feeling,” or the heavy, warm piano march that carries “Horses In My Dreams”? Even the gentle collapse and defeat of “We Float” feels like light flooding your senses in the best possible way. Though it’s unlikely that Polly will ever make anything this purposefully polished again, it’s a little blip of calm in the eye of the larger storm, a moment of shimmering assurance among a back catalog that largely aims to make the listener uncomfortable. Few albums by anyone have captured that precise feeling, making Stories something truly special. —Elise Soutar

259. The Byrds: Sweetheart of the Rodeo (1968)

Considered the definitive moment when hippie rock met country, Sweetheart of the Rodeo marked Chris Hillman’s buddy Gram Parsons joining the band that defined folk-rock with “Turn! Turn! Turn!” and Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man.” Suddenly aligned with a hardcore right-wing genre, stereotypes were shattered—not with Clarence White’s electric guitar, but pools of Jay Dee Maness and Lloyd Green’s plangent steel. Songs from bluegrass stalwarts The Louvin Brothers (“The Christian Life”), hard folkie Woody Guthrie (“Pretty Boy Floyd”) and emerging superstar Merle Haggard (“Life in Prison”) sat comfortably beside Dylan (“You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere”) and Tom Hardin (“You’ve Got A Reputation”) as simpatico companions, making the synthesis seamless. Parsons’ enduring “Hickory Wind,” a wistful song of time spent growing up, embodies what’s to come, stands out along with his “100 Years From Now.” Considered a failure when it was released, the visionary adaptation of country & western with California rock and pop paved the way for the Eagles, Linda Ronstadt, Poco and Emmylou Harris. —Holly Gleason